“If willpower worked, you’d already be done.”

That line hits hard because it’s true in the way that only painful truths are. If brute force self-control was enough, you wouldn’t still be circling the same battle. You wouldn’t be waking up with regret, making “never again” promises, and then—somehow—ending up right back where you swore you’d never return.

And here’s the part most people need to hear before they can change: this doesn’t mean you’re weak. It means you’ve been trying to solve a brain-and-body condition with a tool that was designed for ordinary behavior change.

Willpower is great for things like getting up early, skipping dessert, or finally cleaning out the garage. Addiction is different. Addiction rewires motivation, decision-making, and stress response. That’s why “trying harder” can actually make you feel worse—because you keep using the same approach, and every setback gets interpreted as proof that you’re broken.

You’re not broken. You’re stuck in a system that willpower can’t fix by itself.

The Willpower Myth

Why trying harder works for habits—but not addiction

Willpower is basically “effortful self-control.” It’s you pushing against an urge with your conscious mind. For many habits, that works—especially when the habit doesn’t hijack your reward system and survival wiring.

Addiction does.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) explains that drugs can change brain areas involved in reward, stress, and self-control, which helps drive the compulsive use that defines addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse+1

So when someone says, “Just stop,” they’re imagining addiction like a bad habit—something you can quit if you want it badly enough.

But addiction isn’t primarily a desire problem. It’s a regulation problem:

- regulating mood

- regulating stress

- regulating cravings

- regulating impulsive action when the brain is flooded with urgency

That’s why the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) defines addiction as a treatable, chronic medical disease involving complex interactions among brain circuits, genetics, environment, and life experiences—often continuing despite harm. Default

When you’re dealing with a chronic condition, the solution usually isn’t “try harder.” The solution is treat it like the thing it is.

How the Brain Changes in Addiction

Craving, compulsion, and decision-making

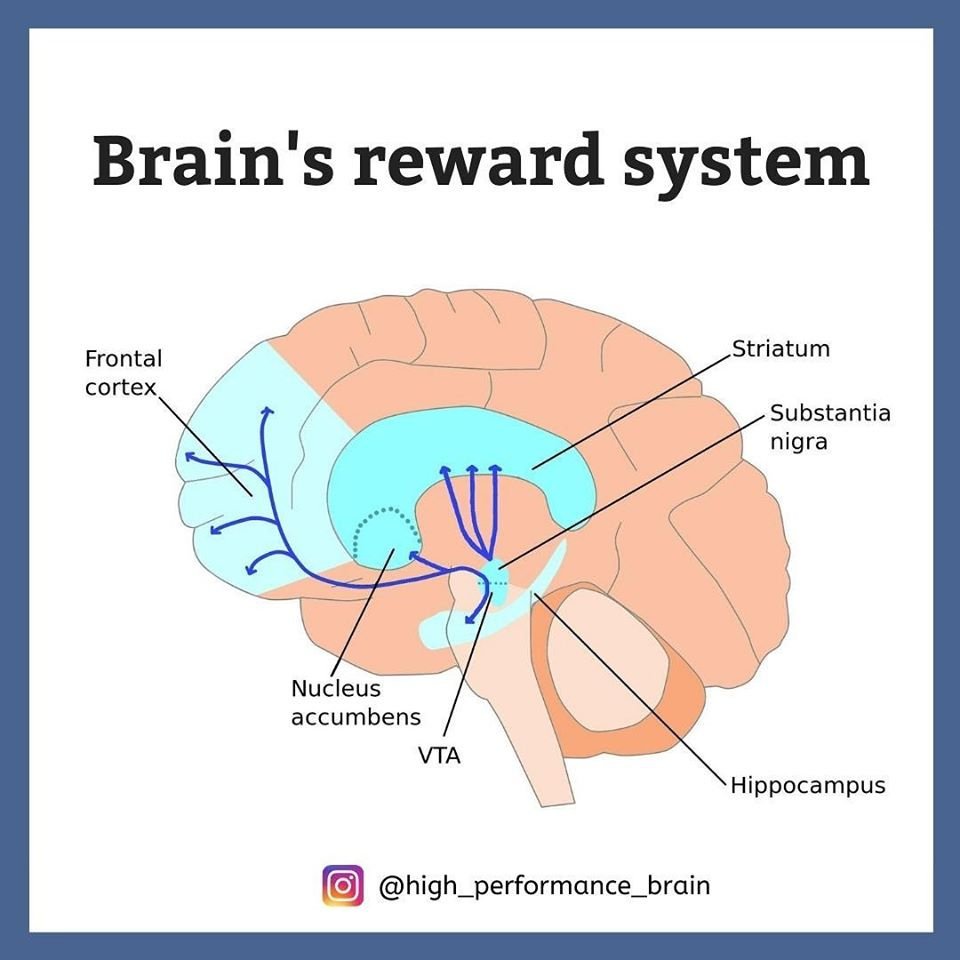

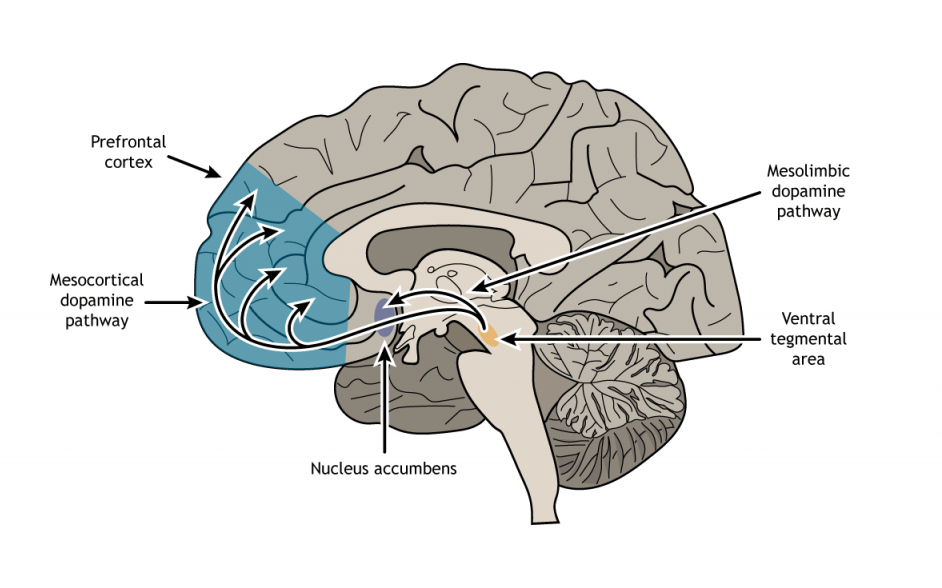

One reason willpower fails is that addiction changes the brain systems that sit underneath “choice.”

A major review in the New England Journal of Medicine (Volkow, Koob, & McLellan) summarizes how repeated substance use can produce neurobiological changes tied to reward, stress, and executive function—helping explain why addiction is compulsive and relapse can happen even when someone genuinely wants to stop. New England Journal of Medicine+1

Here’s a plain-language way to think about what’s happening:

1) The reward system becomes “trained”

Your brain learns: This substance equals relief or reward.

Not just pleasure—relief. That matters. Because relief is powerful learning.

NIDA’s “Drugs, Brains, and Behavior” series describes how drugs can overstimulate reward pathways and strongly reinforce drug-taking behavior. National Institute on Drug Abuse+1

2) Cues become loaded with power

People, places, emotions, times of day—anything paired with using—can become a “go signal” for craving. Research on cue-reactivity and craving shows that exposure to drug cues can activate brain systems linked to urge and attention, sometimes before you’ve even formed a conscious plan. PMC+1

3) Executive control gets compromised

Executive function is the brain’s “management system”: planning, delaying gratification, inhibiting impulses. Multiple neuroscience sources describe how addiction is associated with dysfunction in prefrontal systems that support self-control. NCBI+1

So when you say, “I don’t know why I did it—I didn’t even want to,” that can be literal. In the moment, your brain may be operating on automatic survival logic:

- Get relief now.

- Deal with consequences later.

That’s why willpower—something fragile and effortful—often collapses right when you need it most.

Why Promises Keep Getting Broken

Stress, emotion, and triggers override intention

Most people don’t relapse on their best day. They relapse on their worst day. Or their emptiest day. Or the day they feel exposed, rejected, ashamed, bored, anxious, furious, or exhausted.

Stress is not just “a factor.” It’s often the match that lights the whole cycle.

A classic review by Rajita Sinha highlights stress as an important contributor to relapse risk, examining stress-related processes tied to drug seeking and relapse vulnerability. PubMed+1

More recently, Sinha also reviewed how stress is associated with substance use and SUDs and proposed a framework for understanding stress response patterns and recovery to homeostasis. JCI

Here’s what this looks like in real life:

The promise is made in calm…

You’re clearheaded. You mean it. You feel determined.

But the relapse happens in threat…

Not always physical threat—often emotional threat:

- panic

- loneliness

- shame

- conflict

- grief

- “I can’t handle this feeling”

In those moments, the brain is not asking, “What’s my long-term plan?”

It’s asking, “How do I feel better in the next 10 minutes?”

That’s why your intentions can be sincere and still get overridden.

High-risk situations + low coping = relapse vulnerability

Relapse prevention research (Marlatt & Gordon’s model, summarized by Larimer and colleagues) describes how high-risk situations and the person’s coping response play a central role in whether a lapse occurs. Effective coping and self-efficacy reduce relapse probability. PMC+1

This matters because it reframes relapse:

It’s often not “I didn’t care.” It’s “I didn’t have enough protection and coping capacity for that situation.”

What Actually Works Instead of Willpower

Structure, support, accountability, treatment

If willpower isn’t the engine of recovery, what is?

A better question is: What makes relapse less likely and recovery more sustainable—especially on hard days?

The answer is a system. Recovery is built through repeated structure and support that lowers risk, increases coping, and treats what’s driving the behavior.

NIDA emphasizes that addiction is treatable and that relapse does not mean treatment has failed—similar to other chronic conditions. National Institute on Drug Abuse+1

CDC also frames addiction as a treatable disease and notes that while no single approach works for everyone, treatment options exist and recovery is possible. CDC+1

Here are the big pieces that outperform willpower:

1) Structure that reduces exposure to triggers

Structure isn’t punishment. It’s protection.

Examples:

- deleting dealer contacts

- changing routes and routines

- avoiding high-risk hangouts early on

- not being alone at night when cravings spike

- planning weekends instead of “winging it”

Structure is you building a life where your brain doesn’t have to fight a thousand cue-trigger battles every day.

2) Support that breaks isolation

Addiction grows in secrecy. Recovery grows in contact.

Support can mean:

- peer recovery groups (12-step, SMART Recovery, other mutual-help formats)

- a sponsor or recovery coach

- therapy (individual and/or group)

- family education and support

- sober friends you can call before—not after—the spiral

Even if you’re not ready to talk to anyone, notice this: the moment you consider reaching out, shame often screams, “Don’t.” That’s the addiction protecting itself.

3) Accountability that interrupts the “autopilot”

Accountability isn’t about control. It’s about friction—a moment that slows the relapse train.

Examples:

- scheduled check-ins

- drug testing in treatment or monitoring programs (where appropriate)

- honest relapse planning (“If I’m thinking about using, I will…”) written down and shared

- putting your plan in someone else’s hands when you can’t trust your brain in the moment

4) Evidence-based treatment

Treatment isn’t just “talking about feelings.” Good treatment is skills + stabilization + underlying-cause work.

Depending on the substance and situation, evidence-based care can include:

- behavioral therapies (like CBT-based approaches)

- relapse prevention planning

- trauma-informed therapy when trauma is part of the pattern

- medications for certain substance use disorders

For opioid use disorder, SAMHSA’s TIP 63 reviews FDA-approved medications (methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone) and the additional supports needed to sustain recovery. SAMHSA+1

For stimulant and other substance use disorders, contingency management is one evidence-based approach that has strong support in the research base; U.S. HHS/ASPE has published guidance and discussion on contingency management’s role and implementation considerations. ASPE

The point isn’t “everyone needs the same treatment.” The point is: addiction responds to treatment, not self-hate.

5) A plan for stress—not just sobriety

If stress reliably leads to relapse risk, then “sobriety plans” that ignore stress are incomplete.

A real recovery plan includes:

- sleep protection

- nutrition and hydration

- movement (even a walk)

- emotional regulation tools (breathing, grounding, urge surfing)

- boundaries with people who destabilize you

- a crisis plan for when you’re at a 9/10

Recovery is not just “stop using.” It’s “build a life where using isn’t your only relief.”

Reframing Failure

It’s not weakness; it’s untreated addiction

When willpower fails repeatedly, the most common conclusion is:

“Something is wrong with me.”

But the more accurate conclusion is:

“My approach doesn’t match the problem.”

ASAM’s definition includes hallmark features like impaired behavioral control, craving, and dysfunctional emotional response—exactly the things people blame themselves for. Default+1

So when you relapse, you’re not witnessing your character. You’re witnessing:

- a brain trained to seek relief

- a stress system that flips on fast

- coping resources that weren’t strong enough for the trigger load

- a disease process that needs treatment and support

This is why shame is so dangerous. Shame doesn’t create recovery—it creates hiding. And hiding is where addiction thrives.

Reframing doesn’t mean excusing harm or dodging responsibility. It means telling the truth so you can actually do something effective next.

A more useful question than “Why am I like this?” is:

- What triggered me?

- What was I feeling right before?

- What did I need that I didn’t know how to ask for?

- What support or structure was missing?

- What do I do differently next time—specifically?

That’s recovery thinking.

Gentle Call to Action

“You don’t need more willpower—you need support.”

If you’ve been using willpower as your only tool, you’ve been fighting a war with a pocketknife.

You don’t need a tougher personality.

You don’t need harsher self-talk.

You don’t need one more grand promise you’ll later feel ashamed about.

You need support and a plan that holds up under stress.

If you’re ready to take one small, real step:

- Tell one safe person the truth (even a little of it).

- Call a local treatment provider.

- Go to one meeting (online or in person).

- Ask about an assessment—just an assessment.

- If opioids are involved, ask specifically about medication options and comprehensive support (TIP 63 is a solid reference point). SAMHSA

If you don’t know where to start, SAMHSA’s National Helpline is free, confidential, and available 24/7/365 at 1-800-662-HELP (4357), and FindTreatment.gov can help you locate services. SAMHSA+1

And if you’re in immediate crisis or fear you might harm yourself, call or text 988 in the U.S. (Suicide & Crisis Lifeline) right now. SAMHSA

You’re not weak because willpower isn’t working.

You’re human. You’re dealing with something real.

And you deserve more than white-knuckling your way through pain.